American Pharoah Read online

Page 3

In the afternoons as the races neared, the empty spaces were filled in with men in smart suits and women sporting hats, one more fanciful than the next. The bookies dotted the apron atop makeshift stairs, a smudged chalkboard getting erased and redrawn with the latest odds for each horse in the upcoming field. It was a carnival rolled into a cathedral with all awaiting an act of God handed down from on high, and that’s what Frances witnessed as the horses galloped around the track, disappearing into unseen valleys and then emerging to fly into the air and extend their front legs like Superman and clear impossibly high hurdles. This is what Frances wanted to do with her life—she wanted to help horses like those before her reach levels of full flight that gave horse lovers like herself goose bumps.

That is exactly what she had done. She worked in whatever yard would have her as she pursued a degree in Equine Science at the University of Limerick. She then took a turn in horse sales at Mellon Stud, learning to turn out yearling horses into their Sunday best to attract a big price from bidders at sales held by Goffs, Ireland’s preeminent auction house since 1866. Her next stop was Newmarket, Suffolk, sixty-five miles north of London and widely regarded as the Bethlehem of Thoroughbred racing as well its global center. Horses have lined up against each other there since 1174, and it was King James I (who reigned from 1603–1625) who built a palace there and established racing as a royal pastime that continues to this day. In 1967, Queen Elizabeth II opened a breeding center called the National Stud and remains a frequent visitor to watch her horses train. The people-to-horse ratio is 5 to 1, as the town has a population of 15,000, largely to take care of the 3,000 racehorses.

The Aga Khan, the rulers of Dubai, and the princes of Saudi Arabia are among the top-end breeders and owners who ready their top-flight horses for the European races in England, Ireland, France, Germany, and Italy. It was among the gallops and training trails here that Frances watched Sir Michael Stoute, John Gosden, and Saeed bin Suroor care for and nurture some of the most expensive horses in the world. It was like watching Shakespeare direct one of his plays at Stratford-upon-Avon.

Still Frances wanted to learn more. So it was off to the Bluegrass state, where scores of “lads” (they were predominately men) from the European circuits before her had gone and found a home. Frances did, too.

“One year turned into five years, and then ten,” she said with a lilting brogue.

Now it was fifteen years, most of them here at the Vinery as first the farm manager before becoming the farm’s assistant general manager. Frances, thirty-six, was pretty and blond—there was nothing about her that suggested “farm” or “manager.” However, when you saw her dirty-faced, toting a medical box or her elbows deep into a mare’s abdomen boots pressing into her rump as she helped a foal along, there was no mistaking the fact that she was to the horse farm born. She was totally in charge of the more than 400 acres of rolling hills, veined with limestone and dark plank fences. With its plantation-style big house, spired barns, and groaning weathervanes, it was not lost on Frances that she had landed in a far different world from her humble Listowel. Those limestone fences? They were laid centuries ago by stonemasons from her native country and are recognized as work of masters now, but back then Irish were a rung below the black slaves—“white niggers” the Kentucky colonels called them—and had to settle for the backbreaking work of laborers.

Not anymore. A young Irish horsewoman was in command of every inch of bluegrass here and was valued, even revered, for her dedication and skills bringing racehorses to the track. It was rewarding for Frances to hear Rick Porter, owner of the mare Havre de Grace, the 2011 Horse of the Year, tell people that she was the reason he sent his horses to the Vinery.

“I have never had a trainer not compliment the condition of the horse when they receive it after Frances,” he told top horsemen, always bringing a blush to her cheeks.

That was not why Frances climbed out of bed at three in the morning to check on a baby or sleep alongside a mare all night. She was rewarded when her hands climbed the legs of a yearling checking for heat and not finding any or having her neck unexpectedly nuzzled while rubbing a belly warm. It was the whinny of a hungry mare at feeding time or the barely audible crunch of hay on a late night. She loved those old stone walls too, and would sit atop them and watch the fresh fillies and colts dart in and out of the bluegrass as if trying to figure out what exactly to do with those vibrating legs.

Frances knew she had been blessed as well to have a hand—no, two hands and a bursting heart—in developing wonderful racehorses like Havre de Grace and the gorgeous gray mare Joyful Victory, a Grade 1 winner who raced at ten different tracks. There was the Arkansas Derby winner Archarcharch and the Louisiana Derby champ Friesen Fire. Even better, Frances knew there was no place better in horse racing than being at the center of the industry where hope springs eternal and where horses were simply horses and their owners’ dreams were a long way from being dashed. Each and every one of the approximately 23,500 colts and fillies born in 2012 was a potential Kentucky Derby or Kentucky Oaks winner, a future Horse of the Year, or, God willing, a Triple Crown champion.

The secret was no secret at all but an edict for Frances and her ilk: You treated each and every horse like the gifts that they are and the champs they could become.

In fact, she had a good feeling now about a colt in Barn 9 that liked to spend his summer days in the field on the corner of Spurr Road and Yarnallton Pike. He had arrived in June from Tom VanMeter’s Stockplace Farm to begin his initial lessons on becoming a racehorse and had gravitated to what was the playground for some of the farm’s most promising athletes.

The previous summer it was where a Tapit colt grazed and chased a Pioneerof the Nile colt around. Tapit was an extraordinarily bred horse and already among the most successful sires in the world. He stood at Gainesway Farm for $125,000 and had a handful of classy babies at the Vinery now. The jury was still out on Pioneerof the Nile. Frances was certain, however, that was about to change with this colt out of Littleprincessemma that continued to catch her eye. At first glance, he was exceptional only because he lacked any “chrome,” as the white markings on the feet or face are known. He looked like he had been dipped whole in a vat of mahogany paint except for his black mane and tail. She knew his father well. Pioneerof the Nile was a mainstay of the Vinery, and she had seen a good many of his foals. As important as bloodlines are to creating a quality racehorse, Frances believed that, much like people, certain body types work together. She was beginning to see the type of mare that physically worked well with the stallion.

“He is a big, rangy horse with a classic physique. He displays an exceptionally athletic walk to him and covers a lot of ground,” she said. “Littleprincessemma is compact, ripped even, and has a powerful hind end with good bone and substance. It is a great physical cross. He is long but strong.”

Even as a foal and weanling, Frances saw how easily he moved, his head high, folding and unfolding himself with exquisite balance. His stride had range and scope and he had a lovely sloping shoulder and great body angles. There was nothing out of place on him, especially when he was in flight. The colt shared a field with nine mares and their foals, and when playtime broke out, he looked like a bullet train among steam engines—he was that efficient and aerodynamic. It was the joy he exuded, however, that took Frances’s breath away. One evening on her daily run, she spied him all alone darting back and forth. Suddenly, he bucked and spun, bucked and spun, and then got into a full sprint so quickly that it was as if he had been shot from a cannon.

It stopped Frances in her tracks. “Did I just see that?” she asked herself.

As blessed physically as the colt was, his mind was even more impressive. Of all the mares and stallions on the farm, Pioneerof the Nile and Littleprincessemma were among the most even keel. Despite his precoital quirks, Pioneerof the Nile was a gentle giant who enjoyed the company of people. Littleprincessemma was even more of a softie but still managed to be

come something of a Queen Bee among the broodmares. It was no secret Thoroughbreds were high-strung animals, and it was in the hands of people like Frances on farms like this that get them into a routine so they can take the necessary steps to becoming a professional racehorse. At this stage, it was not much different from raising a baby. They were turned out at night and brought in for the days where they were exercised, bathed, and groomed. Their biorhythms were heeded and the human interaction done on schedule and in small doses. They got their shots and were dewormed. There are sponges and combs pulled over their coats and through their manes. They must be taught how to stand still for a farrier and to hold each foot up to be trimmed. Sometimes it looked like beauty school, but most of the time it was a nursery.

Weaning the foals from their mothers was a critical step in their development and often was fraught with anxiety for both babies and the people like Frances who cared for them. At birth, the foals depend on their mothers for all of their nutrition and the mamas respond by producing thirty pounds of nutrient-rich milk a day for the first two months. Then, feed tubs are introduced filled with sweet feed and vitamin and mineral supplements. At four months of age, a foal will weigh on average 400 to 450 pounds, and it is then they need to be weaned so managed feeding can allow for moderate and steady growth—up to two and a half to three pounds day—putting them in top condition for weanling and yearling sales. The Littleprincessemma colt was in the middle of the weight range and the program Frances designed for the Vinery let the foals stay a little longer with their mothers.

It wasn’t until late June that she started separating the mares, one at time, from their foals. Frances took a mother out every three days or so, watching intently as the baby figured out his mom was gone, but there were still some mares in the field along with all their buddies. Some of them fell to pieces, getting stressed and agitated and finding all kinds of harm: from a nail sticking out of a fence post or twisting an ankle on some uneven terrain. They simply lost their composure and that’s when bad things happened. Frances was eager to see how the Littleprincessemma colt handled the separation. On the day she turned him out without his mother, he was confused for a spell but remained coolheaded, then took to playing with his field mates with his usual enthusiasm.

In a few days, Frances was certain this was a special colt after he walked into the barn, cleaned out his feed bucket, and laid down in his stall for a nap.

She had been around too long to project a blanket of roses being draped on him in the winner’s circle of Churchill Downs on the first Saturday of May 2015. Frances Relihan did do something she rarely did and placed a phone call to Ahmed Zayat. She didn’t know him well.

“I don’t do this often,” she told him, “but the Littleprincessemma colt has been a standout here and I wish you luck with him. There’s something special about him.”

CHAPTER THREE

THE “GET-OUT” HORSE

August 6, 2013

It was fitting that Ahmed Zayat had his true coming out party as one of horse racing’s major players in Saratoga Springs, New York, a town that has long made Thoroughbred lovers weak in the knees and has elicited poetry from some of the great sportswriters of our time. Joe H. Palmer, a Lexington-bred former English professor who wrote the nationally syndicated racing column “Views of the Turf” for the New York Herald Tribune, wrote that “he was no noted lover of the horse, but of a way of life of which the horse was once, and in a few favored places still is, a symbol—a way of charm, and ease and grace and leisure.” The great Red Smith, a Pulitzer Prize winner for the New York Times, put the town’s hold on New Yorkers more succinctly: “You drive north for about 175 miles, turn left on Union Avenue and go back 100 years.” The heart of the town, of course, was the 350-acre Saratoga Race Course, which was veined by white fences and tangled with shade trees that hid barns immaculate enough to look like an equine Ritz-Carlton. From late July through Labor Day, the Spa, as horseplayers called it, was the center of the horse racing universe.

From before dawn until 10:00 a.m., horses stopped traffic on Union Avenue as they clip-clopped back and forth from their barns to their workouts on the racetrack. It was founded in 1863 by John “Old Smoke” Morrissey, a gambler, casino owner, boxing champion, and future U.S. Congressman. It has been devoted to racehorses for more than 150 years and has been the genial host of gamblers since the days of Diamond Jim Brady. It is where the horse Harry Bassett, representing the South, beat Longfellow, representing the North, in the 1872 Saratoga Cup; where Man o’ War experienced his lone defeat in twenty-one starts to a horse fittingly named Upset in the 1919 Sanford Stakes; and where 1930 Triple Crown champion Gallant Fox was beaten by a 100-to-1 long shot named Jim Dandy in the Travers Stakes. It is quite simply the Vatican of American horse racing and where the best bred and most expensive horses usually take their baby steps in their two-year-old year on the road to the Triple Crown.

In the summer of 2007, Zayat was in Saratoga with one of those precocious horses and a whale of a tale to tell about how the colt came by his name. Now, the Spa is no stranger to characters, and over its illustrious history it has been visited by all sorts of them from the muck-raking journalist Nellie Bly to the late Augustine Williams, a retired carpenter from nearby Albany and part owner of 2003 Kentucky Derby winner Funny Cide. While Bly wanted to shut down a town that she considered strictly a sinners’ city, Gus, as he was known, reveled in its vices and was a fixture in the local watering holes, where he passed out a business card with his photograph and title, “Professional Italian.”

Beyond the communion with the horses, Saratoga was the kind of place where your body, soul, and bank account took a beating in the name of a good time.

It’s hard to surprise people there, but one morning the sight of Rabbi Israel Rubin leading a group of students from the Maimonides Hebrew Day School in Albany along the backside of the racetrack on their way to Barn 70 drew second, third, and fourth looks. It was an unusual field trip, conceded the rabbi, but he explained that they had come to see a horse that, like his school, was named for Moses Maimonides. Rubin thought long and hard before arranging to take his students to the track. He did not attend horse races or gamble and worried that the expedition might be considered sacrilegious by his colleagues and parents within his community. Ultimately he decided this was an opportunity for a teaching moment about Maimonides, who lived more than 800 years ago and is considered among the greatest Jewish philosophers. He was the chief rabbi of Cairo and the physician to the sultan of Egypt.

“He blended religious study and intellect with worldly manners to heal the sick and guide the healthy,” Rubin said. “He was respected and honored by both Jews and Arabs. This is especially relevant now in our life and times.”

Zayat had chosen to name the colt that he bought for $4.6 million for exactly that reason. At the time, no one in Thoroughbred circles knew much about Maimonides’s owner, not even the colt’s trainer, Bob Baffert, other than he was new to the game and spending lots of money. The year before, 2006, Zayat’s horses won forty-one races, including a handful of stakes, and he employed a variety of trainers. Baffert passed on his cell phone number and said he believed Zayat had an interesting story to tell. He was in California at the time, and by phone, Zayat explained how he had grown up Muslim in a suburb of Cairo and was waiting for the right colt to name Maimonides.

“He was a very special man who was highly regarded by all people, regardless of faith,” he said of the philosopher. “What has happened with September 11, Iraq and what’s going on in the region is contrary to the way I grew up. If this horse is going to be a superstar, I want an appropriate name. I want to say something with the tool I have, which is a horse. I want it to be pro-peace and about loving your neighbor.”

When Zayat tried to register the name Maimonides with the Jockey Club, however, he discovered that it had been reserved for more than nine years by Earle I. Mack, a New York real estate investor and a former ambassador to Finland. In 19

97, Mack, then the chairman of the board for the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York City, was instrumental in bringing King Juan Carlos I of Spain to New York to accept the school’s Democracy Award. Mack had been moved by the king’s remarks about how much Spain’s culture had lost when the country expelled its Jews in 1492 as part of the Inquisition. The king mentioned Maimonides, who was born in Córdoba, Spain, in 1135 and who, with his family, was forced out of the country while Spain was ruled by Muslims.

“I was just waiting for a horse good enough to deserve the name,” Mack said.

Mack had owned and bred horses for more than forty years and knew that Zayat’s colt, a son of Vindication, was bred to be special. Each also understood the other’s good intentions. Zayat donated $100,000 to Cardozo to commemorate the king’s visit there and to promote tolerance. Mack released his claim to the name Maimonides. Now Maimonides, on the strength of an eleven-and-a-half-length victory in his one and only race, was one of the favorites to win the Hopeful Stakes, one of the most important races for two-year-olds.

“He had the right horse and the right motives,” Mack said. “We are all after the same thing: to touch people across cultures.”

Horse racing is an unpredictable business, and a thoughtfully named horse hardly guarantees future fame and fortune, but this was a nice story, right?

It was until the day it appeared in the New York Times and the phone calls and e-mails began pouring in from members of a synagogue in Teaneck, New Jersey, saying that Zayat was, in fact, an observant Orthodox Jew. It was the first time, but no way near the last, that Ahmed Zayat would offer his version of a conflicting story and continue to make headlines in horse racing.

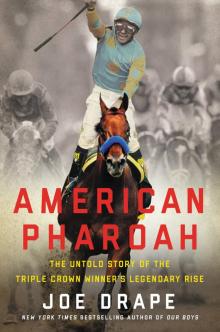

American Pharoah

American Pharoah